Effective nonprofits

The most striking fact about philanthropy to me is how little money rich people give away. It is well known that we all die, and that leaving overwhelming wealth to your children can make their lives worse not better, so the alternatives don't seem that hard for philanthropy to beat. Why do people hold on to the money?

I am not aware of accurate data on private wealth, but as a first approximation this Forbes list says 74 people/family units in America have $10 billion dollars or more in net worth, and only 9 have given away more than 10% of it. 10% of their total wealth is a low bar; I prefer 5% per year as the bar, which is how America thinks about private foundations. So, that’s fewer than 9 out of 74. And hey, perhaps I’m settling for too little even at 5% per year – many religious people with no family wealth and a normal job give away 10% of their income. Some non-religious people too.

For those 74, if you don’t have a plan for hitting >5%/year soon, it just keeps growing and getting harder. Warren Buffett has “only” been giving away at scale for a couple decades – $55 billion over 20 years – and is now stuck with $140 billion aged 94. When he dies, his children will be tasked with disbursing three times what he’s managed to get rid of in half the years.

And Buffett is one of the exceptions, giving away a meaningful percentage every year. The other exceptions as far as I can tell are: Bill Gates, Melinda French Gates, MacKenzie Scott, Dustin Moskovitz and Cari Tuna, George Soros, and John and Laura Arnold. Plus: across his life, Chuck Feeney made $8 billion, gave almost all of it away by 2016, and died last year aged 92. (Please email me if there are people I’ve missed from the list, who roughly fit the criteria of >$10 billion in assets and giving >5%/year.)

I asked three rich people recently why they thought their peers aren't giving away much money. They weren't sure, and agreed it was strange. They each offered hypotheses; some overlapped, some didn't. Perhaps the wealth is held in a founder's company, and the founder doesn't want to shake confidence in that company by selling stock? Or the person/couple/family would feel "on the hook" for what happens at the nonprofits, and doesn't have time to oversee donations to many places properly? One hypothesis recurred in all three discussions, as a potential explainer for non-giving: many people do not perceive nonprofits to be effective, in general, as a class of organisation.

The types of rich people we were speculating about tilted Silicon Valley-ish, so this perception of nonprofits may not surprise you depending on your stereotypes of Silicon Valley, or indeed of rich people generally. But it surprised me. The brushstrokes of "nonprofits aren't effective" were about the level I’d expect for tweets but seemed too broad to be a belief that guides action and inaction in the real world. Plus, the structural limitations of for-profit companies and governments are also well known, but not so bad as to write them off as a group – why beat up on nonprofits?

I have now reflected on my surprise, and suspect some perceptions of nonprofit ineffectiveness come from familiarity with particular types of nonprofits, and negative associations some people have with those types.

Starting close to home: familiarity via visualising "nonprofits" as the amorphous subcontractors of San Francisco County's $10 billion+ annual budget, working on societal problems like housing without much progress to show over the previous decades. “I see a lot of problems around me still, so clearly whatever is being tried isn’t working.” Second: visualising nonprofits as Harvard and other famous universities, receiving donations to build another lecture hall. Third, visualising the Red Cross and Salvation Army and other massive charities, where the work feels positive but it's hard to know what your donation really changes since it’s <1% of their operating budget.

Grants to nonprofits can have asymmetric upside, with impact that persists across society long after they’re made. Philanthropic grants were key to:

- inventing the Pill. Contraceptives were controversial in 1950s America and there was little government funding for research or interest from pharmaceutical companies. Thank you Katharine McCormick for funding almost the entirety of the development of the first oral contraceptive

- researching high yield strains of wheat and other crops that led to the Green Revolution, breaking the necessity of lifetime subsistence farming for hundreds of millions of people and preventing millions of deaths from starvation. Support from: Ford Foundation and Rockefeller Foundation

- establishing gay marriage as legal in the U.S., via state-by-state campaigning, ballot initiatives, and lawsuits. Support from: Evelyn and Walter Haas Jr. Fund, Gill Foundation, Arcus Foundation, and others

- getting rid of most battery cages for farmed hens, so they aren't trapped between metal bars for their life. Support from: Open Philanthropy and others – work still to be done though, this one's recent and the transition is not complete

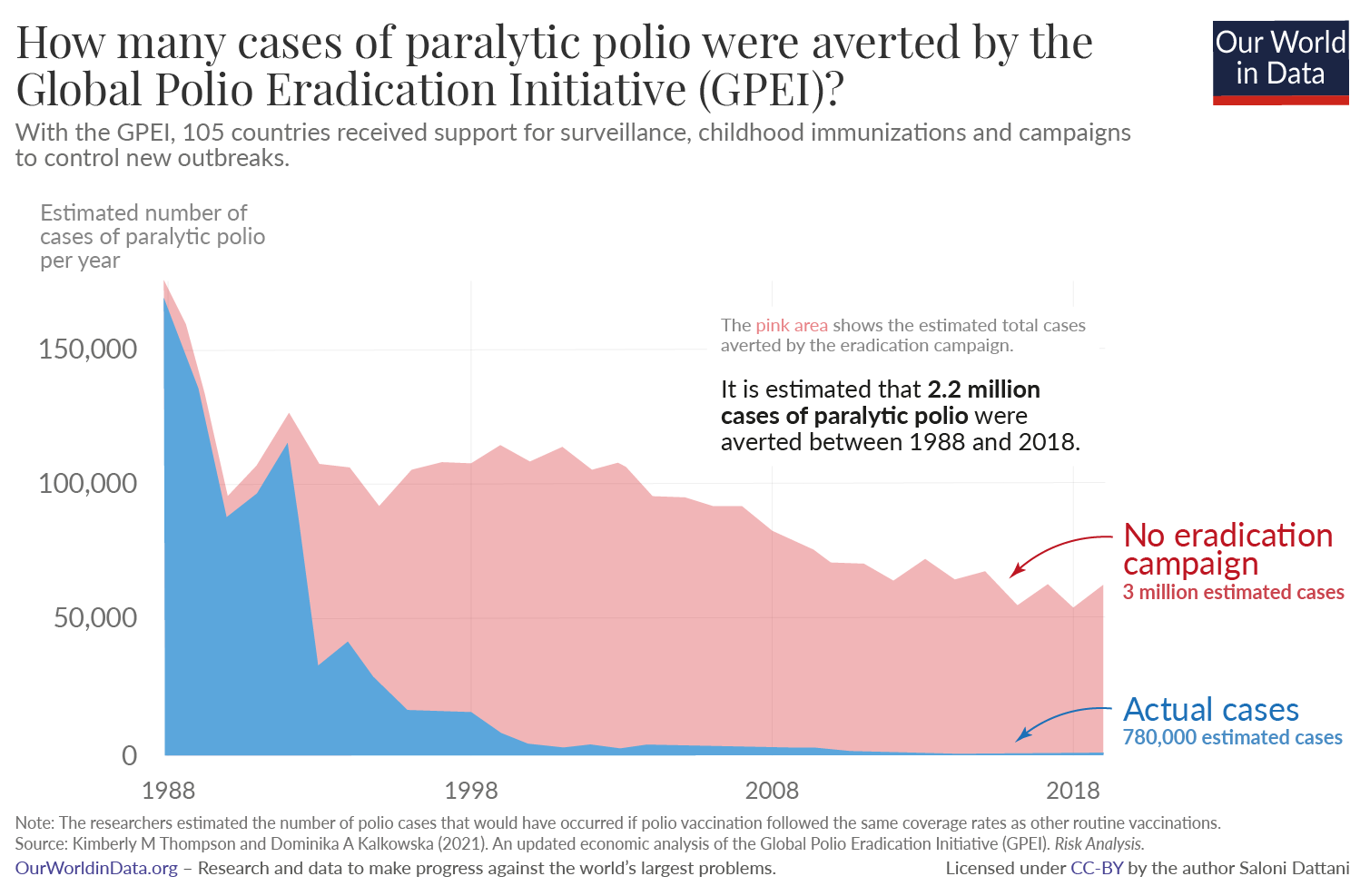

- driving polio down near to eradication. Support from: many individual donors contributing to Rotary International, and the Gates Foundation

Philanthropy can fund research that governments won't touch, or are too risk averse to fund. Nonprofits can work on problems that affect people who don't have much money, where for-profit companies would not make much profit. Nonprofits can provide public goods, or campaign on social issues, in an organisational structure that makes sense for the shape of those problems.

The examples above are enough historical proof that nonprofits can be effective, even if they say nothing of the median nonprofit’s effectiveness. History can offer evidence, but it does not provide a list of what to support today.

Here is a (very) nonexhaustive list of nonprofits that have helped achieve prosocial outcomes, that do not currently have enough funding to achieve their greater ambitions. I’m splitting them up crudely by what they do into research and development, goods and services, and information and advocacy.

Research and development

My other blog posts are about scientific problems traditional forces in society aren’t solving, so click around for more in this category (though philanthropy isn’t the solution to all such problems). There are over a hundred academic labs we have supported at Open Philanthropy over the last eight years, so I'm banning myself from listing any labs for fear of favouritism, and sticking to nonprofits (not just Open Phil grantees, and in no particular order):

- CARB-X and GARDP develop new drugs to fight antibiotic resistance globally. If you donate to CARB-X, they regrant the money to whatever the most promising, currently-unfunded development project is in the field so you don’t have to be an expert or do the vetting. GARDP mostly develops antibiotics themselves

- Good Food Institute supports R&D on plant-based and cultivated meat to reduce emissions and provide alternatives to factory farming

- International Vaccine Institute runs clinical trials of new vaccines for diseases we don’t have good enough vaccines for yet, but that aren’t that lucrative for pharma companies

- Medicines for Malaria Venture develops new malaria drugs in time before drug resistance wrecks the ones we currently use

- Convergent Research starts “focused-research organisations” on particular scientific problems that aren’t a good fit for academia or a for-profit startup

- DNDi and Medicines Development for Global Health develop new drugs against neglected tropical diseases

- NEST360 conducts/funds research to prevent neonatal deaths in hospitals

Goods and services

- Malaria Consortium distributes preventive malaria drugs to kids at risk of infection, in countries like Nigeria, Burkina Faso, and Mali

If you stared at the picture at the top of this post, and couldn’t look away from the greens, consider a trip to Uganda, to Murchison Falls National Park. You should take preventive malaria drugs while you’re there to be safe. The pills should be easy to pick up from a pharmacy before you set off.

What about the kids who live near the National Park, say in Masindi? Those drugs are cheap, but aren’t free. Ten years ago, hardly any kids in Masindi, or in Uganda, or in sub-Saharan Africa, got preventive drugs, even those who might get infected with malaria multiple times a year in high transmission areas. Tourists visiting for a week got more protection because they’re richer.

Today, 50 million kids get preventive drugs in the malaria season:

Around one third of those kids – more than 16 million children – get drugs through Malaria Consortium programs that are philanthropically funded:

But what about 6 to 10 year olds, not just under 5s – should they get protected too? And should preventive drug programs expand to more areas? That takes money, and health ministries already have other important programs to cover. New donors needed.

Perhaps you noticed Uganda is a tiny slice on the top of that happy graph, despite being home to 8 million children under the age of 5. There is not a malaria season in Uganda, unlike in much of West Africa; infections are year round. Seasonal malaria chemoprevention went from rare to common in the last decade, for kids in West Africa. Children in Masindi still do not have access to the drugs that a tourist passing through has, on that drive up to Murchison Falls.

- GiveDirectly sends money to people in the U.S. and other countries (as a donor, you can choose which), for them to spend on whatever they want

Thousands of people in Bangladesh, Kenya, and Uganda have had their incomes doubled by GiveDirectly donors, enabling them to buy bikes, fix up their houses, open shops, buy clothes for their children, eat better food, and meet many other needs that would be difficult with more prescriptive donations.

What about people in other villages with unmet basic needs, that GiveDirectly hasn’t reached? What about families in rural Nigeria? New donors needed.

- Gavi helps pay for basic childhood immunisations in countries with stretched public health budgets

Gavi is so big that I wouldn’t recommend it for normal donors – only governments and someone from the list of 74 above. But unless someone decides to step up to change the game, Gavi doesn’t have enough money to support e.g. seasonal flu vaccines, or the new RSV or dengue vaccines, or (in my opinion) to be sufficiently urgent and ambitious about rolling out the new malaria vaccines.

- Helen Keller International funds campaigns to get vitamin A supplements to kids, to help prevent blindness and support development of early childhood immune systems

- International Refugee Assistance Project provides legal services to refugees and displaced people to help them navigate complicated asylum systems

Information and advocacy

This category largely consists of public goods that would be unusual for companies to provide given the work benefits society rather than customers and shareholders. I’ve subdivided the category further, but the unifying theme is that the change you're trying to effect happens through another group you’re aiming to persuade or help (often, national governments), rather than through a nonprofit's direct activities.

Information, data, knowledge

- Our World in Data collects and visualises datasets on how the world works, and on pressing global problems like poverty and climate change

- Institute for Replication systematically reproduces social science research to see which results hold up

- Epoch AI tracks trends in artificial intelligence to inform public discussion and policy

- Policy Cures Research tracks data on neglected disease R&D, to inform government funders and philanthropic foundations

- CarbonPlan tracks data on carbon offsets and carbon dioxide removal projects

- National Academy of Sciences produces reports that synthesise scientific understanding on a given topic for a policy audience

I would put investigative journalism in this subcategory too.

Technical assistance to governments

- J-PAL and Evidence Action help governments scale cost-effective interventions to reduce poverty and improve health

- Clinton Health Access Initiative assists health ministries in low- and middle-income countries to implement new programs

- Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination creates regionally tailored resources on hepatitis B and C, and helps governments tackle chronic infections

- Engineers Without Borders provides engineering services to local communities and sometimes governments to build lasting infrastructure (e.g. sanitation, energy, transportation)

- Lead Exposure Elimination Project helps governments regulate and remove lead from paint and other sources

Advocacy

- Open Wing Alliance advocates that restaurant chains and supermarkets switch their supply chains so eggs don’t come from hens in battery cages, and holds companies to their pledges

- Friends of The Global Fight advocates for full commitments from donor governments to the Global Fund, to support malaria, TB, and HIV/AIDS programming globally

- 1Day Sooner organises and advocates for volunteers in high impact infectious disease trials

Think tanks and policy development

I’m not going to write a list in this section, because different readers may think particular think tanks are effective, but pushing in the right or wrong direction depending on their favoured policies. So, choose your own. (That said, I can’t help but mention the Institute for Progress and Center for Global Development in the U.S.)

Many nonprofits are effective at achieving important goals. If you are wary of nonprofits from one context, avoid those ones. They should not make you wary of impressive nonprofits working in other areas. In fact, some of the more interesting work that shapes our collective future starts as eddies in those calmer pools, small groups protected from party politics and quarterly earnings reports working on something that matters, even if just for a few years, before larger forces pull them out to sea again.

Thanks to Quintin Frerichs and Andrew Bergman for comments

[1] Most of my blog posts are written from the "societal" perspective, of what problems are valuable to work on. The societal lens on the topics in this post would ask different questions than I have asked. Should governments tax rich people more, and if so which types of taxes should go up? What types of organisations should be able to receive tax-deductible donations, if any? Should investments in prosocial/R&D-intensive sectors like biomedicine receive preferential tax treatment? Should donor-advised fund accounts (or equivalents in non-U.S. countries) have minimum annual payouts, since they function in many practical respects as private foundations? I often end up finding the societal lens more interesting, so I will probably return to it in future posts. Thanks for bearing with me in this interlude.

[2] Other American donors who didn’t meet my >$10bn wealth, >$5%/y donations inclusion criteria based on public data, but came close: Mike Bloomberg (>$10bn donated, and some of the work supported seems great), Barbara and Amos Hostetter (Barr Foundation), Jeff Skoll, Pierre Omidyar, Lynn Schusterman, Edythe Broad, Jim Simons, George Kaiser, and Donald Bren. Possibly Laurene Powell Jobs, anecdotally, but I haven't seen good public figures on the total $ she's given away. I’m smudging by including Laura and John Arnold on the main list, since according to Forbes they have <$10bn (maybe true, maybe not, don’t know) – but they’re doing lots of proactive thinking and giving in a way that feels "frontier" to me in the philanthropy sector, so I wanted to include them. I'm also squinting at the 5% line for some on the main list; hard to know exact figures, there's year by year variation, etc.

[3] More philanthropy success stories: seven wins, fifteen wins, history of philanthropy web publication, 100 philanthropy case studies in a book. For more on the philosophical and political questions, here’s a book on philanthropy’s role in society.