FDA, ARPA-H, & CDC – policy ideas part 2

CDC

6. Start convening ACIP Work Groups on diseases/infections that have no vaccines, many years ahead of there being particular candidates to assess. Publish the rough parameters under which ACIP would expect to recommend a vaccine rollout.

[This whole post is personal, not written as part of my job.]

Before I explain what I mean, here are six areas where this idea would help: gonorrhea, chlamydia, herpes, Zika, norovirus, and CMV. None of those have vaccines. It would help with the 4 vaccines on the 10 unmade technologies list too: hep C, adult TB, syphilis, and strep A.

Now an explanation. The FDA is a regulator: it decides what medical products can legally be bought and sold. Once something’s legal to sell, people still need to know whether to buy it – no regulator can tell you that. In the case of vaccines, there’s a committee that debates the merits and value for money of new vaccines when one gets near the finish line, called the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). That committee then makes a recommendation to the U.S. government.

If ACIP says a vaccine is worth it for kids, the Vaccines for Children program ($6 billion annual budget) will cover the costs for parents who can’t. If ACIP says a vaccine is worth it for older people, Medicare will pay for it; for people covered by Medicaid, Medicaid. Any private insurer legally has to follow ACIP recommendations too, and offer you a vaccine for free if you want it and you’re at a clinic/hospital/pharmacy in their network.

That means if you’re making a vaccine, you don’t just grit your teeth for a letter from the FDA that tells you your fate after twenty years of work. You also listen in sweat-drenched and fidgeting to one of ACIP’s three annual public meetings, where the attendees discuss whether your vaccine’s any good.

Not many biotech startups or pharmaceutical companies or even academics are working on strep A vaccines. But if ACIP recommended that a future strep A vaccine be integrated into childhood schedules, that vaccine would, in addition to helping many kids, become a blockbuster. So, will ACIP recommend a universal rollout, or something narrower? We can’t know until there’s a particular vaccine under consideration, with data from clinical trials to debate.

There is plenty to debate ahead of time, though, to reduce the uncertainty: let's say future clinical trials show a vaccine prevents strep throat 70% of the time, but there's no available data on whether it reduces the deadly invasive forms of strep A infection. That's enough of a reason for the FDA to approve the vaccine, but is it enough on its own to roll out the vaccine to everyone? If it's not, what evidence would help bridge the gap – a randomised trial showing the vaccine reduces hospitalisations too, suggesting nastier infections are being stopped? Next: let's say the vaccine lasts a year, and you need annual boosters after that. Would that be worth it for kids, or too much of a hassle?

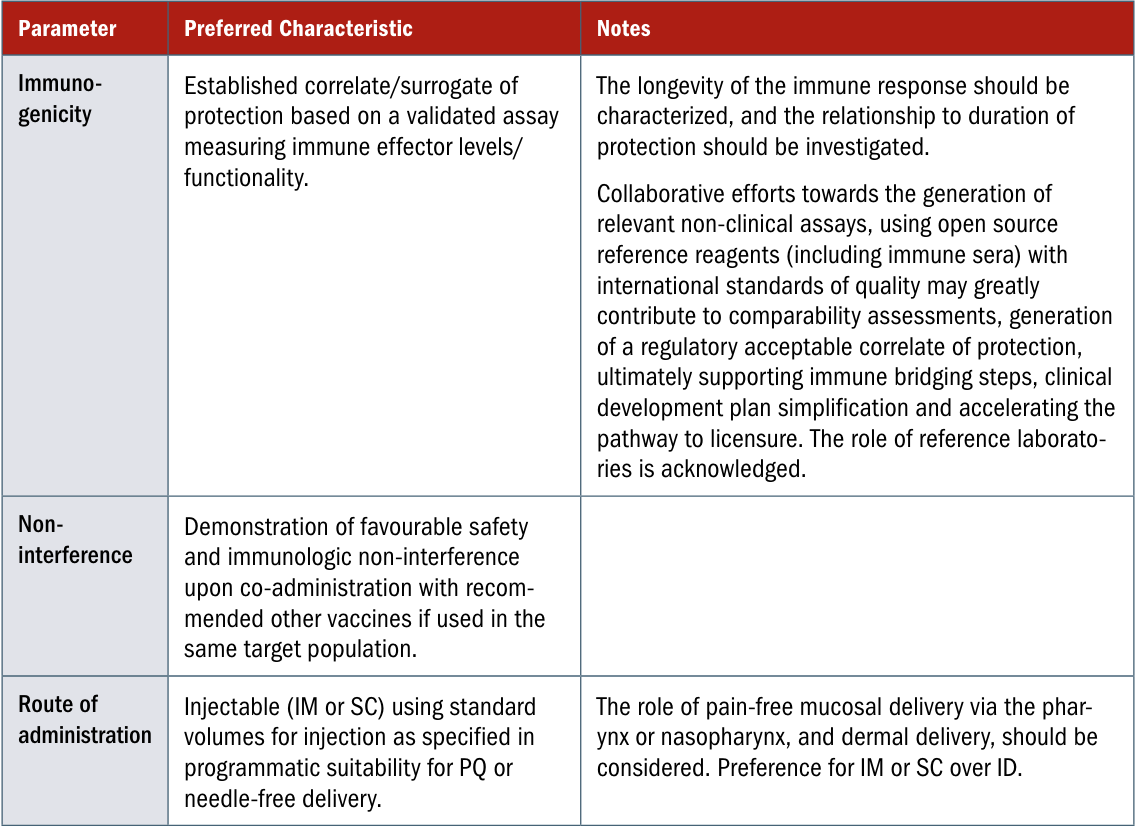

These are questions that should be modeled out and debated now, so that vaccine developers can assess how much energy to devote to strep A research, and design their clinical trials – booster regimens, endpoints, age range – with ACIP’s guidance in mind. ACIP could either report out the qualitative results of such a Work Group, or adapt BARDA's approach and formalise their expectations into a Target Product Profile.

These two product classes, at least, are ready to start the process:

- Strep A vaccines. A useful starting point is the Preferred Product Characteristics report WHO published in 2018, though there will be some adaptation to do for the American context, and new evidence to integrate since then:

- Hepatitis C vaccines. Under what conditions would a hepatitis C vaccine be recommended broadly? What about to particularly at-risk groups? What about to people who are on treatment or who have completed treatment, but may otherwise get reinfected?

These assessments would provide valuable information absent any additional financial carrot for inventors. That said, some would pair well with advance market commitments, to create an incentive to invent pathfinder vaccines sooner, if those vaccines meet ACIP's conditions. In other words, I hope Congressional staffers stuck around after part 1...

(I am not positive ACIP is the best home for this work, though I suspect it is. NVAC might be instead, since it also sets vaccine strategy for HHS, or the FDA might be, since they are used to requesting TPPs from drug developers as a guide to communicating what success looks like during a particular application process.)

FDA

7. Sign Confidentiality Commitments with more countries, and broaden the scope of existing commitments, so we can share useful information when those countries make requests – for faster and better drug approval decisions in those countries.

Remember the redactions that led to policy suggestion #2 in the last post?

My suggestion there was to create a track to share Neglected Tropical Disease product reviews, unredacted. I assumed, though was not sure, that Congress getting involved would help. Here’s a complementary change that I believe, though am not sure, the FDA could do on its own – a change that is broader. Redactions don’t stop at sleeping sickness, and they don’t stop at malaria.

If someone cures hepatitis B (#7), they’re probably going to apply to sell that cure in the U.S. first, because they will be able to make billions of dollars and will have investors to pay off who funded the trials that proved the cure worked. The fact plenty of people have hep B infections over here means, definitionally, it’s not a Neglected Tropical Disease – so that track isn’t relevant. But lots of people in Brazil and Indonesia have chronic hepatitis B infections too. The company will hopefully approach other health regulators shortly after us.

The FDA has a budget of around $6 billion per year and 18,000 employees, many of whom are PhD scientists. The Indonesian medical regulator has a budget of around $150 million per year, and fewer staff. The first thing the assessor who gets assigned that drug application will want to do is call up the FDA and ask to see our inspection report, with the reasoning for why we decided to approve it here. Probably a lot of that reasoning is relevant to the Indonesian population too. Here’s how that phone conversation currently goes:

🇮🇩: Hey, this is Indonesia calling. We just got an application for a drug that’s FDA approved already. Out of interest, what made you decide to approve it? We’re thinking of doing the same.

🇺🇸: Great to hear from you! I can’t tell you that.

🇮🇩: Pardon?

🇺🇸: You can check our website, we post our reviews there, but whatever’s there is all we can share with the public.

🇮🇩: I clicked around a bit, but the review isn’t up yet for this drug. And for previous drugs, the documents you uploaded looked pretty helpful but blocked out some information I’ll need – I might get in trouble if I don’t have the full picture, something goes wrong, and the drug harms a patient here.

🇺🇸: Sorry, those redactions come from our legal division. They're mostly removing confidential business information from the company who applied. You could be a competitor.

🇮🇩: O.K., got that. But I think I mentioned – I’m actually a regulator of a sovereign nation with 275 million people in it? And 10 million of them have chronic hep B infections, and the company we’re talking about literally wants to sell the product here? Anyways, don’t worry, I mostly just wanted to check – is the manufacturing site they’re applying to us with the same one you did an inspection of? Then we can skip our inspection, we trust you guys.

🇺🇸: *rustling candy wrappers into receiver* You’re breaking up.

The FDA representative does not want to be this awkward, but they have to follow the rules. The Indonesian representative doesn’t want this – and while there is more variety to consider from the drugmaker’s point of view than with the NTD track, often the company doesn’t want it either. Their clinical sites and manufacturing site already got pored over by FDA inspectors – are Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Thailand going to send people too? Hosting those visits would take all month, and the inspectors are going to ask mostly the same questions, look at mostly the same equipment, interview mostly the same staff.

So, holding aside a bigger transparency overhaul, the goal is: allow FDA to treat other regulators differently to the general public, and share more. We're already two steps towards that goal. First, in 1993, FDA issued a rule that allowed it to share some information with other foreign regulators that it doesn't with the public (Page 61598) – though not trade secrets without the company's permission. That’s if those countries sign a two-way confidentiality agreement with the U.S., confirming they won’t publish the unredacted documents either – the first of which were signed in 2003 (page 28).

It’s not always clear what information a company considers a trade secret. Product formulas can be trade secrets. Any ingredients not on the product label might be a trade secret. Maybe the type of bioreactor they used is a trade secret... So the FDA errs conservative and redacts a lot, in part, I assume, to avoid any risk of getting sued. But Indonesia needs to know, Brazil needs to know, what they’re actually approving, and how it was made. So the second step taken by Congress, in 2012, allows the FDA to stop redacting trade secrets too if an appropriate, more stringent agreement is in place (page 1071).

Great! Why weren’t those two steps enough? Why am I still complaining? It is true we share documents, we receive documents – but not enough in either direction for the sake of patient benefit and timely reviews: "in 2022, FDA received 20 documents from foreign regulators related to 11 marketing applications and shared 76 documents related to 52 marketing applications."

Three suggested changes:

- Many countries do not yet have any confidentiality commitment with the FDA. Unfortunately, these are often countries where medical need is highest, and the U.S. acting as a reference regulator would be most helpful. Where’s Ethiopia's agreement, Malaysia's, Vietnam's?

- -> FDA leadership should set aggressive goals to complete more two-way Confidentiality Commitments with lower- and middle-income country regulators.

- Many of the agreements that have been signed are limited. E.g. our agreement with Indonesia is with the Fish Quarantine and Inspection Agency. That sounds like the Food bit of the FDA and not, you know, the drug regulator?

- -> Extend the scope of existing commitments, when they’re limited, to allow sharing in more areas – especially related to drug approvals.

- The FDA has only made use of the trade secret flexibility from Congress in agreements with one continent: Europe. That's what the final column "FDCA 708(c) Authority" refers to in this table. What all the "No"s in that column mean are that, even after an agreement is signed, redactions will reign.

- -> Extend 708(c) authority to more country agreements, not just those with European countries, to allow sharing of full documents that include trade secrets.

8. (I think?) Start accepting data from clinical trials conducted outside of the U.S. more frequently, and be open to approving more drugs that have no clinical data in the U.S., so long as the trials are representative.

Why? Drugs are invented and tested around the world, and plenty of those drugs would benefit Americans, but they may never get submitted to the FDA due to fear of rejection when none of the data comes from U.S. patients. (It costs $4 million to apply, after all.) If an inventor does decide to include a U.S. clinical site to improve their chances, it may take years to complete trial recruitment for diseases that aren't that common. Those are years when patients are suffering, that could be avoided if other countries helped out.

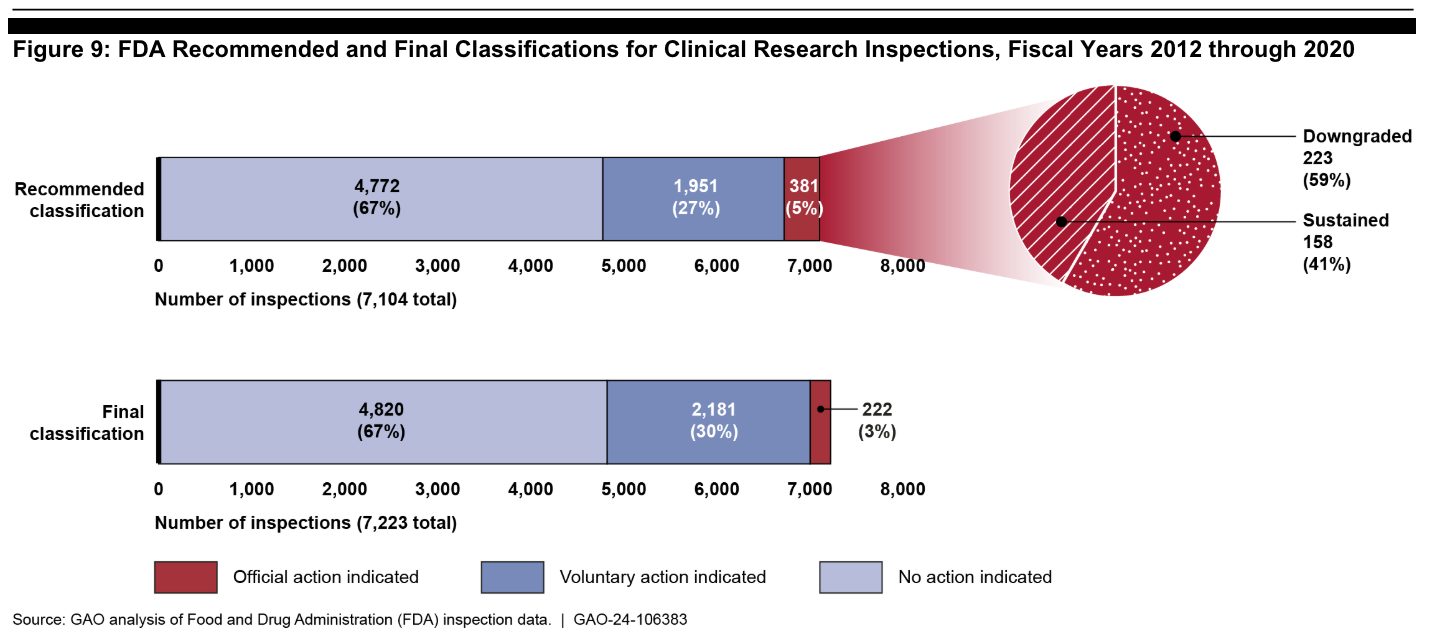

My "(I think?)" hesitancy comes from not having more friends who have assessed New Drug Applications and Biologics License Applications, or worked as FDA clinical research inspectors. My experience of the tradeoffs isn’t that grounded, and I'm at risk of pontificating. Indeed the FDA does accept foreign data frequently – two thirds of clinical trial investigators for FDA brand name drugs are based in foreign countries (though most inspections are domestic, page 21 and 22). All that said, I’m pretty sure this is the right direction to lean, and it’s an important topic that cuts across medical progress for all diseases.

There are three main reasons the idea of accepting more foreign data makes people nervous. It makes American public health officials nervous because there is a perception that trials run in America tend to be higher quality with more trustworthy results. It makes the medical research community nervous that what worked over there won’t work over here because people live different lives, smoke more, weigh less, and so on. Then it makes people in other countries nervous that pharma companies are going to start testing products on their fellow nationals for the benefit of Americans, not for them, since America is where you can make the most money. All three of these relate to real dynamics that need to be navigated. But the current approach hurts both Americans and foreigners, so it’s time to navigate them!

On the first: variation in quality of trial management is real, but there are high quality clinical trial sites and Clinical Research Organisations (groups you pay to run the trials) everywhere these days. And we have plenty of low quality, underpowered trials right here too.

On the second: it’s true, you have to be careful about variation in comorbidities and other background factors that differ between countries. You should be careful how you interpret any data; some populations are underrepresented in trials to their detriment; and the broader the representation usually the better. But at the end of the day, humans are more similar than they are different, which is why clinical trials have any external validity beyond the trial population in the first place. Data from a U.S. phase 3 trial was good enough for other countries that wanted the Moderna COVID vaccine.

(One thing I’ve often wondered, but found hard to make precise enough to answer: does human biology differ less between individuals than human desires? Is that why the scientific method is better suited to medicine than other sectors of the economy?)

On the third: accepting more out-of-country data should benefit countries where the clinical trials are based, too, if ethical protocols are followed. For one, it will help the scientific workforce in that country. People rightly worry about patients first, though: pharma companies testing drugs in one place then flying away and never making them available there would be immoral. Paragraph 34 of the Helsinki protocol ensures participants in a trial get access to the trial drug if it turns out to work. That helps, though it doesn’t obligate the company to make the drug available to everyone in that country who might need it, which is the problem. Companies should be making serious attempts to register their product for sale in the countries where they ran the studies; governments and civil society should hold their feet to the fire and call out bad behaviour if they don’t. (I would be interested in seeing data on how often non-registration happens. Were I a journalist, I’d be professionally interested.)

9. Consider moving some efficacy evidence requirements to post-licensure (while maintaining high standards on safety and drug quality pre-licensure) for: programmable pandemic therapeutics, tuberculosis vaccines, and hepatitis C vaccines, due to inherent difficulties in clinical evidence generation.

Here are some FDA programs that already exist: Fast Track for serious conditions (introduced in 1988), Accelerated Approval when it’s appropriate to use surrogate endpoints for those (1992), Priority Review so you get a response within 6 months not 10, which is what the Neglected Tropical Disease voucher program is based around (1992), and Breakthrough Therapy if you can show substantial improvement over what’s already on offer (2012). Even slicker, the Animal Rule, when it’s not ethical to collect efficacy data in humans so you go for approval on human safety and animal efficacy data.

This combination has enabled progress on vaccines in particular, thanks to flexibility from CBER, the part of the FDA that regulates biologics (a category that includes vaccines). I have you to thank for my monkeypox vaccine – I appreciate it!

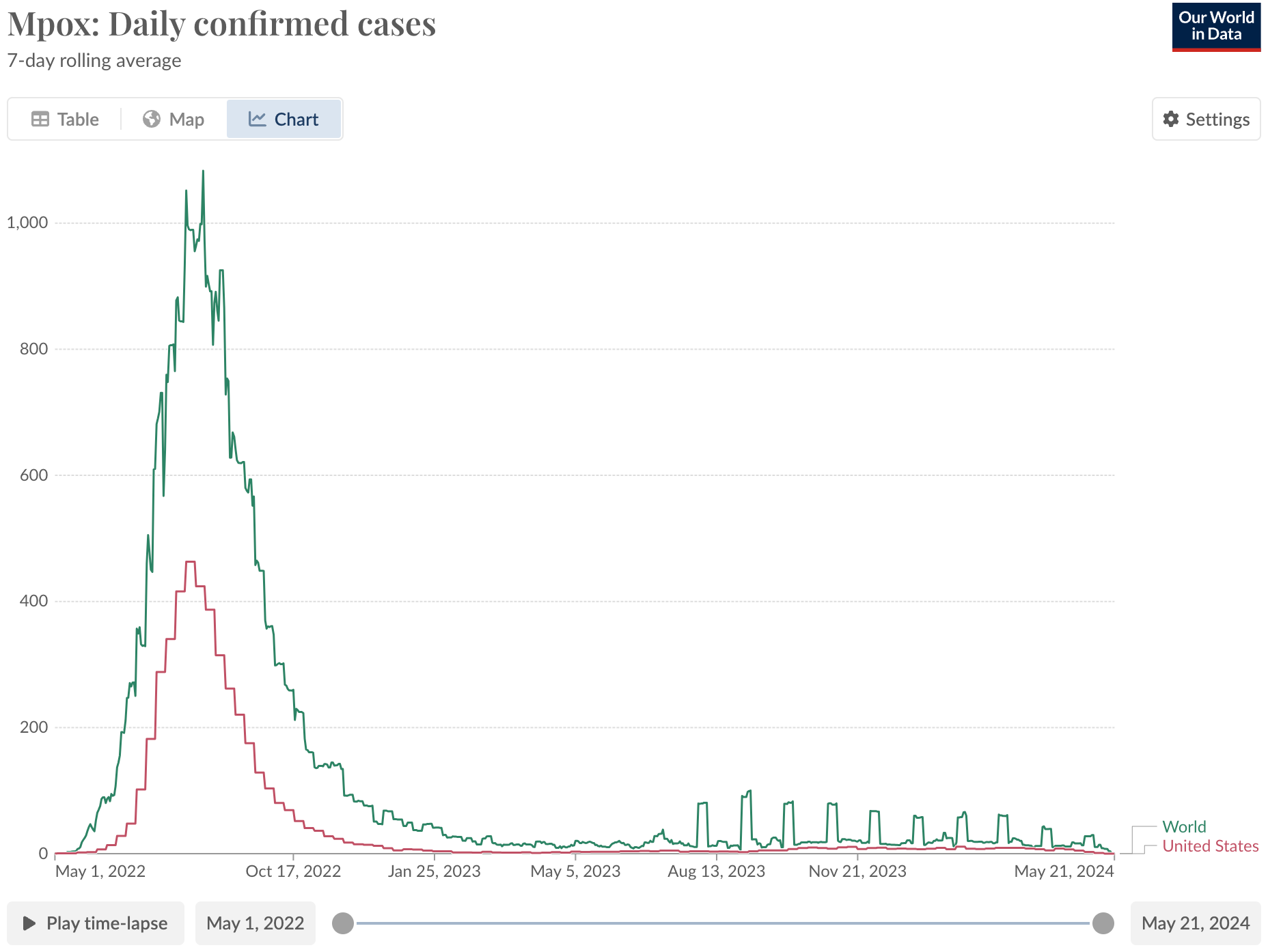

I have mixed feelings about that graph, since a deadly form of mpox is going around the Democratic Republic of Congo right now; "confirmed cases" are not the same as actual cases. There is less testing infrastructure in the DRC, so most infections go unreported. Nonetheless, the case is striking as a vaccine policy success in the U.S.:

The mpox vaccine was already approved in 2019, on human safety data, human antibody data, and data showing it protects primates exposed to the virus. The application received Priority Review, i.e. was reviewed quicker than "normal" drugs, then won a voucher when it got approved that the maker sold for $95 million. That meant the vaccine was already being manufactured when there was an outbreak in the United States. In addition to the FDA’s CBER, credit to BARDA for purchasing those vaccines, despite some rollout issues in the first few weeks.

My gay friends were lining up for 2+ hours to get that vaccine. None of them knew that the evidence it worked was weaker than for COVID vaccines, until I told them (I didn’t have a blog back then so they bore the brunt). Then few cared because it probably works and you might as well get it since it’s safe. That vaccine was part of the reason the graph above looks so happy, so far. That achievement is seriously cool and should be celebrated.

Two further examples of creativity from CBER: they approved Vaxchora on efficacy data from challenge studies under Fast Track and Priority Review (+ it then won a voucher). And they approved Valneva’s recent chikungunya vaccine, graced by the holy quintinity: Fast Track, Breakthrough, Accelerated Approval, Priority Review, and a voucher ($103 million).

All of this is to say, there’s not a "standard" path that all vaccines and drugs must follow to reach approval; regulatory paths can adapt to constraints imposed by reality. Here’s how FDA could be creative for pandemic therapeutics, adult tuberculosis vaccines, and hepatitis C vaccines:

- Making use of the Animal Rule, or similar principles, would help for drugs that may be "broad spectrum" enough to defend us against several possible future pandemic pathogens. A path to licensure is especially important if those drugs are options for the national stockpile. Otherwise, getting leads "phase 2 ready" ahead of time may be enough, rather than needing licensure.

- Incidence of lung disease (the type of TB that kills most people) outside of particular places like mines in South Africa and prisons in Russia and Brazil is (happily) low, so it is difficult to statistically power a trial with clinical endpoints – "clinical" meaning observations of actual disease, not a proxy like levels of antibodies in your blood. Yet correlates of protection for TB – e.g. antibodies – are not well characterised, so using those is not (yet) a good option for trials either. This is a tricky spot to be in, as a regulator. The fact TB is mostly a problem outside of the U.S. should not lead to the FDA lowering its standards – as always, we should only approve things that we’d approve for people in the U.S. (Whether other regulators hold the same standards is up to them; it’s not our business.) So the question is: what evidentiary standards on efficacy should be required to approve a vaccine for Americans (travelers, immigrants from high burden countries, people who live with someone on treatment). There is no existing vaccine, so the need is high. That means a vaccine shown to be safe, with low certainty on efficacy, should still be legal to sell and to take. That may mean FDA reviewers accepting lower pre-specified statistical power (75%?) and more flexibility on confidence interval thresholds (0% efficacy lower bound? 10%?) than "usual". By "usual" I'm thinking of RSV and COVID trials, but I shouldn't be – there is no "usual"; mpox vaccines had less human data than I’m suggesting and were a gamechanger! CBER can put further requirements post-licensure, for the company to monitor and report back on.

- For hepatitis C, vaccine approvals on human safety data + efficacy data from controlled human infection models (CHIMs) alone may be possible, if the CHIMs being established in the next few years provide adequate evidence (it’s too early to say). Vaxchora for cholera sets a good precedent, approved on CHIM data. (Similar reasoning applies for Zika, where human challenge models are being set up and incidence is currently low. Zika drugs/vaccines are not on my list of 10 technologies, though, hence the parentheses.)

ARPA-H

10. Someone reading this apply to be a Program Manager at ARPA-H, focusing on ambitious, discontinuous funding of clinical research for hepatitis C vaccine candidates.

This one is not a policy change. It is a call for individual action. Perhaps that individual is you.

ARPA-H was founded in 2022 to attack health problems with a new scientific funding model, and it has been calming to see Congress’s appropriations for it each year since. Now ARPA-H needs to staff up with Program Managers: high autonomy individual funders with particular visions for changing a field. Click around if that sounds intriguing to you. If you don’t have a technical background, send that link to any friends who do, who you think might be interested.

Not many hepatitis C vaccine leads have made it to clinical trials before, because animal models aren’t great for hep C, making a vaccine to Good Manufacturing Practice standards (GMP, required for injecting a human) costs millions of dollars, and recruiting and follow-up for efficacy trials is difficult. Many of the people affected by chronic infections inject drugs and have irregular contact with health systems.

Academics at the University of Toronto and University of Oxford are now looking to establish safe protocols for studies involving intentional exposure to the virus, which should offer a deeper understanding of correlates of protection and a way to distinguish vaccine efficacy for the first time. Separately, the structure of the key E1E2 glycoprotein complex was recently solved. Perhaps I am overly optimistic, but those two facts intersecting could lead to a Cambrian explosion of vaccine leads to be tested in safety trials – "could" if the money and ambition is there. Perhaps even a platform trial with a shared control group to compare leads to each other head-to-head (now I’m really in the clouds).

Regular ol' NIH could do some of this in theory, but (1) paying for GMP manufacturing of many vaccine leads for parallel testing isn't their bread and butter, and (2) other unrelated applicants in the relevant study section might pip some of those vaccine leads to the post (only ~10% of projects that apply to the infectious disease arm of the NIH get funded). Pharma companies could fund some of this work too, and will likely get around to it eventually – but being first in a category is always tricky, and head-to-head comparisons aren't as easy either since academics or competitor companies hold IP for the other leads.

So: now is the time for discontinuous hep C vaccine funding. That may make sense across 2025-30, but not before (the challenge models aren't ready), and not afterwards (if this Program Manager succeeds, pharma can finish the job).

For readers already at ARPA-H... my 2c is a successful applicant would need to be technically experienced and flexible, but I do not think they'd need a background in hepatitis C in particular in order to achieve results in a program of this shape (though it would help), and they would not need a PhD (though understanding vaccine development and immunology is needed).

Bonus policy changes

These aren’t related to the 10 technologies on the list, my framing prompt, so they don’t get numbers. But they'd be nice:

- CDC catch up to the UK on gonorrhea vaccines. ACIP discuss whether licensed vaccines that use the outer membrane vesicles of meningitis B should be recommended for use against gonorrhea too, before the results of the Bexsero phase 3 trial come out – then retract the recommendation if those results come out null. There is observational evidence that Bexsero works somewhat, and lots of safety data already. I asked my doctor for the vaccine and he said my insurance didn’t cover it.

- FDA (on behalf of the HHS Secretary) add Cryptosporidiosis and Shigellosis to the tropical disease list, as argued by the Cryptosporidiosis Therapeutics Advocacy Group. Well, that group argues for adding Cryptosporidiosis – I doubt they’re at loggerheads with Big Shigella, though. Crypto and Shigella both cause around 100,000 deaths a year, mostly from kids who get diarrhea; while they pop up in the U.S. here and there, they’re not big killers. There is no vaccine for either, and the only existing treatment for crypto, Nitazoxanide, is not very effective when given to malnourished kids. Recent epidemiological studies, in particular GEMS, revealed crypto is a bigger killer than previously thought. I doubt anyone would disagree that these two diseases should be added to the tropical disease list; it’s more a matter of catching up to the newer research and papering the decision. (Please email me if I’m missing something! Guidance for inclusion says diseases on the list should have <0.1% prevalence in developed countries; crypto and Shigella have 0.2%-0.3% incidence in the U.S., according to my quick calculation – but infections are brief, so prevalence looks <0.1% for both.)

- Congress pass a bill to correct market failures in the development of new antibiotics, e.g. something like the PASTEUR Act, as recommended by the Center for Global Development, CARB-X, and many others.

That’s it?

There is plenty more the U.S. should change about how we conduct medical research – and how we can be better siblings to developing countries – beyond these 10 ideas. For Americans reading this post, it is our duty not to take the status quo as a given. We could live in a much better world, where preventable diseases don’t kill people, rich or poor. Science is complicated, aid is complicated – but we can get there, we can try, ten suggestions at a time.

Thanks to Tom Kalil and Javier Guzman for comments, and many others for discussions

If you are interested in working on any of the ideas in this or the previous post, I would love to hear from you. jacobtrefethen [at] googlemail [dot] com

[1] There are rough analogues to the FDA and ACIP's dual regulatory + policy recommendation functions in other places too. In the United Kingdom, there’s the medical regulator MHRA, then there’s the vaccine advisory committee JCVI that advises the UK government. The WHO isn’t a country, but it has analogous-ish duality with the prequalification system (which carries out similar activities to a regulator, like site inspections), and SAGE.

[2] Considering phrasing only, the awkwardness level will get actually get worse after we have a broader confidentiality agreement with Indonesia. The FDA person will have to open the call with: "The information you are about to receive is being shared with you pursuant to the Confidentiality Commitments signed by our agencies; the information is non-public information and must be treated as such." (page 20)

[3] The FDA ideas in these two posts could be bolstered by a broader signal from Congress that the FDA’s mission involves helping and being helped by other country regulators ("reliance", "reference regulator", "conditional reciprocity"). What goes around comes around, and playing nice will help Americans get new drugs, cheaper drugs, faster too. In other words, Congress could add global leadership to FDA's mission statement. Longer term, Congress could also encourage FDA to twin with Nigeria and/or ECOWAS and/or the African Medicines Agency, too.

[4] Policy idea #7 draws heavily from a comment in Science on FDA transparency, from four people who used to work at the FDA.

[5] Perhaps I am being unambitious in suggesting more sharing with other regulators rather than more transparency with the public. FDA's CDER division tried a pilot program to share more publicly, and discontinued it in 2020. I'm not sure what to make of that.

[6] BARDA doesn’t get its own subheading in this post because I don't have any suggested changes for them related to the 10 technologies. But BARDA is key to whether the U.S. succeeds on programmable pandemic therapeutics, one of the 10 technologies.

[7] The mpox vaccine example is another one where "global health" research ahead of time protected Americans too. Indeed, depressingly moreso than people in sub-Saharan Africa over the decades since the virus was discovered. There’s a reason a vaccine against SARS-2 was designed two days after the sequence was shared online: a decade plus of SARS-1 research, based on outbreaks in non-U.S. countries, meant scientists knew targeting the spike protein would probably work for COVID, since those spike proteins looked similar.