Science writing from the last two years that stuck with me

This list consists of writing that ticked two boxes: 1) did I think about the article again more than a week after reading it?, and 2) was it written for a popular audience? So, academic papers, including review papers, don't count. Books are out too. Blog posts, magazine articles, essays, interviews, all allowed.

I do not agree with all of the arguments in these pieces. In fact, some frustrate me, leave me with unanswered retorts, or otherwise disturb my peace. Some I think are brilliant and wonderful and perfect.

And this is not a complete list. My apologies to writers who have affected my thinking that I'm forgetting as I type on this particular day!

- A primer on why microbiome research is hard, Owl Posting (Abhishaike Mahajan). You always remember your first Owl Posting piece, and this was mine. My enduring thoughts a year later are: 1) yeesh, how do you design good experiments to get at causality between gut bacteria and diseases, when there's no such thing as a "normal" microbiome?, 2) and when you can't perturb a real human microbiome that well, 3) and we're not even thinking about the funguses and viruses down there... yeesh, yeesh, complicated, oof.

- Will protein design tools solve the snake antivenom shortage?, Owl Posting. You always remember your second Owl Posting piece, and... OK this was not my second. It's more recent, covering research at the Institute for Protein Design that Open Philanthropy (among others) helped fund. I find pieces useful that make the connection between frontier science – even frontier applied science – and the final boss: messy real world problems. The impact of new antivenoms is tricky because the composition of snake toxins vary 1) between snake families, 2) between snake species, 3) between snakes of the same species, and 4) within the same snake as it ages!

- Universal Antivenom May Grow Out of Man Who Let Snakes Bite Him 200 Times, Apoorva Mandavilli, The New York Times. Excruciatingly human pairing to the artificial drug design approach discussed above. I more often read Mandavilli's newsy work, and enjoyed this profile format for a change of pace. This line, in particular, is one for the ages: "On Sept. 12, 2001, crazed by the terrorist attack of the previous day and by the death of a friend a few days earlier, he let himself be bitten by two cobras."

- German patient vaccinated against Covid 217 times, Michelle Roberts, BBC. Similar energy to the 200 snakebites (HT Otis), and a dry opening line: "A 62-year-old man from Germany has, against medical advice, been vaccinated 217 times". Then the results: "The man appears to have suffered no ill effects, researchers from the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg say." Makes me feel like a baby, one of my Pfizers took me out.

- Twenty years of Addgene, Ariana Remmel, Nature. Addgene is a nonprofit repository where scientists can send their plasmids, then Addgene handles requests from other labs who want to use them. This retrospective made me think about which parts of the scientific ecosystem are best served by non-profits, by for-profits, or simply by academic labs themselves. Who should pay for the plasmids, how should they pay (grant to Addgene? slices from labs' project grants? from university/department budgets?), how much, and what setup makes it most likely labs will send research materials to enable their findings to be reproduced? What happens if a repository's revenue model isn't sustainable enough and they shut down one day? Some of these questions come up for other science infrastructure and public goods no individual lab can cover the cost of, like datasets. Who should pay to keep the Protein Data Bank going into its sixth decade?

- The Practical Guide to Biotech Partnerships, Lucas Harrington. I love detailed pieces written by people who've successfully done the thing they're writing about. The more specific the better. Scroll down to the four tables. Specific! Then the societal impression this piece left me with: Mammoth Biosciences is as ambitious a Silicon Valley biotech company as you can get – CRISPR, straight out of Jennifer Doudna's lab in Berkeley, you see their building on the way from the airport to SF – and yet even then it takes time, so many negotiations with investors and larger companies and employees and universities, to get a drug to patients.

- How to Speedrun a New Drug Application, Santi Ruiz interviewing Grigory Khimulya, CEO of Alvea, for Statecraft. OK I take it back, this startup went more Silicon Valley. See also Max Schons', James Smith's, and Kirsten Angeles' 6-part series on drug development, from their experience at Alvea and elsewhere.

- On Modality Commoditization, Elliot Hershberg. Small molecule manufacturing is commoditised, and recombinant DNA/monoclonal antibodies are getting there: "What’s interesting to note is that across each generation [of company], the magnitude of the businesses decreases by roughly one order of magnitude. The first movers grew into ~$100B+ companies [Genentech, Amgen, Regeneron]. The leading service providers that followed became ~$10B+ companies [Adimab]. Now, the new entrants in the discovery market are ~$1B+ companies [FairJourney Biologies, OmniAb]. To me, this looks like the textbook definition of commoditization, which is the gradual process of making a good or service into a commodity and competing on price." It's a long piece with several interesting points beyond that one. I knew about the Chinese lead in manufacturing, but alongside "Will all our drugs come from China?" by Alex Telford (linked near the top of this Hershberg piece), this post woke me up to just how stark the trend in clinical trials is too. As of the last few years, China is eating our lunch, and it may be scraps for dinner.

- The Mouse as a Microscope, Alex Telford, Asimov Press. This one's about how organisms turn into commodities (model organisms). "The majority of lab animals (about 95 percent) are mice or rats. However, the mouse’s modern prevalence was not guaranteed from the outset. The early supply of mice for research depended on a late-19th century community of hobbyists—fanciers—who collected, bred, and sold unusual mice varieties. ... Black 6 is the most popular strain of mice used in research today, but its status as a standard is due to little more than chance. Because it became popular early in the history of mouse fancying, a great body of research and methods were published using the black 6 mouse, which locked in its continued use." Many scientific questions are poorly served by this lock in.

- Introducing Zoogle: An Organismal Search Tool, Arcadia, trying to solve that problem. "Over 90% of research funded by the NIH can be claimed by one of six canonical research organisms (calculated based on these informative posts), < 0.0001% of what biology has to offer." This post explains Arcadia's tool to help you search through which of 62 organisms might be helpful for what you're studying.

- Back to Alex Telford, Some questions about biotech that I find interesting. The questions in his list I come back to most are #2, #4, #11, #22, and #26.

- A Big Misconception About the World's Greatest Infectious Killer, Katherine Wu, The Atlantic. For months after I read this it'd pop into my head, and I'd splutter: what the %$&@? The "fact" always cited that 2 billion people are latently infected with TB is false, and it's "only" hundreds of millions? Or epidemiologists don't even know which?? We're talking about the biggest infectious killer! What the fuck!

- Kamal Nahas has had a run on several infectious disease topics (among other topics) in Asimov Press, that I'm going to merge into one bullet, starting with a pair on TB: The Forgotten Pandemic and The Long Road to End Tuberculosis. Also The Origin of Adjuvants and Making a "Miracle" HIV Medicine.

- How a Big Pharma Company Stalled a Potentially Lifesaving Vaccine in Pursuit of Bigger Profits, Anna Maria Barry-Jester, ProPublica. Bringing together TB and adjuvants, with original reporting on the $500 million phase 3 trial of M72/AS01E.

- Rarely is the Question Asked: Is Our Children Learning?, Lauren Gilbert, Asterisk. Admittedly part of why I remember this piece so well is the title still makes me chuckle. Lauren checks in on what's next, now that most children globally attend primary school. Work still to be done: "Somewhere between 70-80% of children in primary school in a low-income country cannot read a simple story. More than half will still be unable to read by age 10." (This piece is more development economics than physical sciences; bit of deviation from the rest on the list.)

- How one rabid kitten triggered intensive effort to contain deadly virus, Lena Sun, The Washington Post. This is where I learned that many people are stopping me from getting rabies who I never knew to thank: “After Stanley’s death, USDA wildlife biologists spent 10 days trapping and vaccinating animals — 753 raccoons, 41 skunks, four feral cats and one red fox — in an area about 61 miles around where the kitten was found. … The USDA drops about 10 million doses of oral rabies vaccine a year from planes and helicopters in a band of 16 states stretching from Maine to Ohio and south to Alabama and Texas.”

- We Can’t Let ‘Experts’ Decide the Morality of Making ‘Humanized Animals’, Wesley Smith, National Review. Opinions on bioethics vary widely and our current system seems both too conservative and too liberal to me. I'm quite unsure on most of the fundamental questions of the field, to be honest – who should count as an expert? what kinds of decision-making power should those people have vs scientists who wish to conduct experiments? what role should public opinion vs technical opinion play in which types of research are allowed by law? by academic/industry norms? in which types receive public funding? etc. Here's a podcast from Leah Pierson and Sophie Gilbert, Bio(un)ethical, if you want to start down the rabbithole.

- Deliberate Dysentery, Jake Eberts interviewed by Asimov Press. Happily, bioethicists did let Jake Eberts voluntarily get dysentery – for science, and more specifically for kids who may need a future vaccine. Jake live-tweeted the saga, and I followed along parasocially with my friends, our hearts in our throats when he stopped tweeting for 12 hours (he had, indeed, gotten dysentery). He recovered and lived to tweet another day. Since then, I have been fortunate enough to meet Jake in the real world, and in that capacity I can confirm he is still alive. See also "I got dysentery so you don’t have to" from Eukaryote Writes Blog. It's in fashion.

- Seven things you didn't know about life expectancy, Saloni Dattani. The first thing I didn't know about life expectancy is that "life expectancy" usually refers to a lagging statistic, period life expectancy, rather than a present-but-incomplete cohort life expectancy. So it's likely underestimating what reality's got in store for most of us, by several years. That gave me pause, contemplating my future. Then contemplating my present, I blushed at my knowledge deficit, given my job frequently involves quantifying health outcomes. (Luckily my colleagues were ahead of me when I posted this article in Slack.)

- Why we didn't get a malaria vaccine sooner, Saloni Dattani, Rachel Glennerster, Siddartha Haria, Works in Progress. I tweeted about this one a lot at the time.

- On malaria vaccines generally, I feel like I've been in a long distance mind meld with a few dozen people who really care about the issue and have been screaming into the wind. So I'm not sure which things I learned from whose pieces specifically. Some that stuck with me collectively: 1Day Sooner's work, led by Zach Kafuko, e.g. in Foreign Policy, David Wallace-Wells in NYT, Alex Tabarrok in Marginal Revolution, Ben Kraus in Slow Boring, Andrew Joseph's long piece in STAT with lots of original reporting "Behind the malaria vaccines: A 40-year quest against one of humanity's biggest killers". Ryan Duncombe, Karam Elabd, and Justin Sandefur at CGD with their practical modeling around the ambition gap: "Malaria Vaccines: Turning a Scientific Triumph into Millions of Lives Saved"

- Then one more from Stephanie Nolen in the NYT, which I loved in particular because she got people on record criticising some of the mistakes over the last decade. That can be hard, when global health funding is scarce. But we need to look at the past with clear eyes so we can do better today.

- The Gamble: Can Genetically Modified Mosquitoes End Disease?, another Stephanie Nolen malaria piece in NYT, this time on gene drive. Actual reporting from Sao Tome! Finally! Instead of pieces asking abstract questions to people in the US and Europe.

- Egypt Wiped Out Hepatitis C. Now It Is Trying to Help the Rest of Africa., another another Stephanie Nolen, The New York Times. For whatever reason, that guy in the photo stuck with me the most. The photographer was Natalija Gormalova, whose art you can see here. Egypt is ahead of the rest of the world, including the United States. The fact that hepatitis C is now curable but will lead to hundreds of thousands of deaths this year is a painful statement about the limits of even excellent technology, when it meets the complexity of the real world.

- How to start an advance market commitment, Nan Ransohoff, Works in Progress. Every few months I open this piece up again, when I'm feeling stuck on an unsolved technical problem. Jacob, just run the problem through the criteria in part 1, and determine whether AMCs might be a good fit to help solve it. As with Lucas Harrington's guide above, I again like specifics from someone who's done it before, in this case the details on offtake agreements in section 6.

- Machines of Loving Grace, Dario Amodei, and the responses from Stephen Malina and Adam Marblestone and Niko McCarty. I have a post in drafts that tackles some of these topics more head on. In the meantime, for those wondering if San Franciscans are all the same, FYI I disagree with some parts of Amodei's piece that are pretty important to his conclusions. I talk about AI and science in the middle of this interview I did with Alexey Guzey. My thoughts on the intersection keep evolving, so I can't guarantee I'll believe all of what I said in that interview in a few more months!

- The End of Disease, Derek Lowe, In The Pipeline blog (Science). A scientist's retort to Silicon Valley. Lowe's pieces over the years – of which he links out to many in this recent post – emphasise to people who don't work in drug development how hard drug development is even after you have a promising candidate to test. So, if AI helps you discover better candidates at the front end, he argues, that's not enough.

- Protein design meets biosecurity, David Baker, George Church, Science. I've thought about this one for a year and I'm still not sure what I think about it! It locates biosecurity risk not in AI and protein design, but in recombinant DNA itself. Michael Nielsen reaction thread.

- The Making of a Biosafety Officer, David Gillum, Issues in Science and Technology. A perspective on biosafety that starts from one practitioner's point of view, reflecting on his 28 years so far. Emergencies are not always how they first appear. "In late December 2009, when I was the biological and chemical safety officer at the University of New Hampshire, the campus veterinarian called to say that a local 24-year-old woman had been diagnosed with gastrointestinal anthrax. ... A few days later, we heard that the patient had been exposed to anthrax in the campus ministry building while dancing as part of a drum circle. A team from the EPA and FBI had discovered that some of the drums used hides that had not been treated before they were imported to the United States. They believed that the drumming caused the anthrax spores to become airborne, exposing the individual. No one else became infected."

- There was a cluster of pieces over the last couple of years, many in Science, on scientific fraud. They washed over me as a whole, so I'll call out the constituents in one bullet: doctored images in Alzheimer's, more doctored images in Alzheimer's, more doctored images in Alzheimer's. Investigating potential manipulated data, this time in stroke, where the treatment group in a trial had a higher early death rate.

- OK, there's more, make that two bullets: Theo Baker, a student journalist, in The Stanford Daily, on falsified data in Alzheimer's, leading to the resignation of the Stanford President. A Baker NYT op ed. Then here's a more recent piece I haven't read by Charles Piller in STAT, that a colleague tells me I should: "How the ‘amyloid mafia’ took over Alzheimer’s research". I just bought Piller's book on the topic.

- The Origins of “Confidential Commercial Information” at the FDA, Joseph Daval, Aaron Kesselheim, Viewpoint in JAMA. I ended up blogging about the FDA's approach to confidentiality (#2 and #7). Tl;dr it keeps too much confidential, from other governments and from the public.

- How America Built the World’s Most Successful Market for Generic Drugs, Alex Tabarrok. Short.

- Olivia Goldhill and Meghana Keshavan's reporting on MDMA for PTSD in STAT, here and here. How should you design clinical trials when therapy is part of what's being being provided, not just a drug, and when the drug in question puts people in suggestible states?

- Malaria drug discovery by Wendi Yan in Asimov Press, and Dylan Matthews in Vox. Tu Youyou, the discoverer of artemisinin, was elected to the US National Academy of Sciences this year.

- Lessons from Humira, Stephen Malina. "There might be something to the idea that truly groundbreaking drugs take longer to develop. Humira, GLP-1 agonists, AAV gene therapy - they all took decades. Is this a pattern, or just cherry-picking? I'm not sure yet, but it's got me thinking."

- Regulators almost killed biotech before it began, Trevor Klee. What struck me most about this one is I read the same book Klee did and had quite differently-emphasised takeaways (my summary #6 here).

- Metascience Since 2012: A Personal History, Stuart Buck. "This essay is a personal history of the $60+ million I allocated to metascience starting in 2012 while working for the Arnold Foundation (now Arnold Ventures)." Particularly on-target for my job, since I work at a different foundation now trying to carry the metascience torch forward.

- Resolving the Deworming Paradox: Rethinking Deworming Campaigns for Children, Witold Więcek, Center for Global Development blog. He just... solved the worm wars??? With statistics????

- How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Intelligible Failure, Adam Russell, Issues in Science and Technology. Russell was the initial head of ARPA-H, and before that worked at DARPA and IARPA. He knows what the ARPA model is good for vs not.

- Some thoughts on causality in biological systems, José Luis Ricón Fernández de la Puente. José's writings often, to me, read at the boundary of philosophy and science. In a practical and productive sense. What does it mean to reverse aging? You'll get into all sorts of avoidable fights about rapamycin if you don't think about that question clearly. (Rapamycin is a small molecule, of course it can't reverse aging of your cells in every way your cells relate to chronological time.) This piece on causality in biological systems is a classic of the genre, and also reminds me of "Does X cause Y? An in-depth evidence review".

- Tasks and Benchmarks for an AI Scientist, Sam Rodriques. This post is 27 months old, so not within my self-imposed 2 year remit... it's the first of two posts I'm squeezing in illegally. I like how specific and first-person this is. As an outsider, I find the questions Rodriques poses to his AI helper easier to get an intuition for than quantitative benchmarks of AI performance – though those may well be more useful for insiders designing AI systems.

- A Report on Scientific Branch-Creation: How the Rockefeller Foundation helped bootstrap the field of molecular biology, Eric Gilliam. I sort of assume that at some point in my life I'll have a Warren Weaver phase, and I appreciate Eric G's attempts to trigger one in all of us. On the one hand, what a track record. On the other, the science funding world works very differently now to the 1930s, so I'm not sure how repeatable his approach is. On the third hand, going back to that track record... I'd love to see benchmarking vs a counterfactual of what research the Rockefeller money might have funded under a different PM, and when scientists would have gotten around to molecular biology absent Weaver. ;) In any case I have the Weaver biography on back-order after Eric plugged it on a recent podcast. (This is the second of two posts I'm cheating on – published 29 months ago, not 24.)

- How Virologists Lost the Gain-of-Function Debate, M. Anthony Mills, The New Atlantis. Polarising issue between scientists and policy people, where much of the "discourse" goes toxic, so credit for the calm writing when the writer is bound to get yelled at.

- Scientific Publishing: Enough is Enough, Seemay Chou. Polarising issue within science, where some scientists see a glorious vision of the future unshackled by distortions imposed by academic journals, and others see this move as extreme or against scientific freedom. Seemay: "I no longer believe that incremental fixes are enough. Science publishing must be built anew. I help oversee billions of dollars in funding across several science and technology organizations. We are expanding our requirement that all scientific work we fund will not go towards traditional journal publications. Instead, research we support should be released and reviewed more openly, comprehensively, and frequently than the status quo." I can confirm I'm not the only one jostled by this piece, because within 24 hours of my posting it on Slack, a colleague who no longer works in science responded with three pages of reflections.

- How to be a wise optimist about science and technology?, Michael Nielsen. A tricky and abstract topic, which nonetheless guides many people's orientations to policy questions so calls out for grappling. For my part, I struggle with people who de-emphasise science and technology's role in getting the human species on our way out of disease and poverty, and I struggle with people who forget nuclear weapons could destroy cities tomorrow. Nielsen reads as a scientist holding those tensions seriously, alive and vivid, while believing intellectual progress and reconciliation between them is possible.

- My techno-optimism, where Vitalik Buterin coins and defends "defensive acceleration" or "d/acc". I viewed this as coalition building between online factions that saw each other as enemies. The factional responses were almost more interesting than the blog's content – everyone seemed to like the post?

- Training enhances the value of new technology, Matt Clancy, New Things Under the Sun. Shoe-leather reporting from the frontlines of economics of innovation papers.

- Why haven't biologists cured cancer?, Ruxandra Teslo. Biology is complicated. Ruxandra: "fundamentally, if I had to pick just one factor that I think is holding biology back, I would say 'long feedback loops', as argued in this piece by Stephen Malina. Baked into this assertion is the premise that we cannot simply 'understand' biology from first principles, in the same way we do for physics, and all we can hope for is iterative cycles of experimentation. Thus, the faster these cycles, the more surface area we will cover. In a domain like biology, we should expect diminishing returns from extra intelligence and better predictions, with a much bigger bottleneck being the speed with which we can test these predictions."

- Salt, Sugar, Water, Zinc: How Scientists Learned to Treat the 20th Century’s Biggest Killer of Children, Matt Reynolds, Asterisk. This piece starts further back in history, but I'm left amazed (again) by how recently the basics of scientific knowledge have made it into lifesaving global practice. "The Mahalanabis study accelerated the adoption of oral rehydration therapy. In May 1978, the WHO’s diarrheal disease group met in Geneva and recommended a global program for ORT. Within a couple of years nearly 200 million sachets of ORS were being produced, at a total treatment cost of less than 50 cents per patient (compared with more than $5 for intravenous therapy). ... 'Science in the development of these things is a progression,' says Cash. 'It’s not a sudden moment and then everything changes. It doesn’t work that way.'" Dr Richard Cash died just last year.

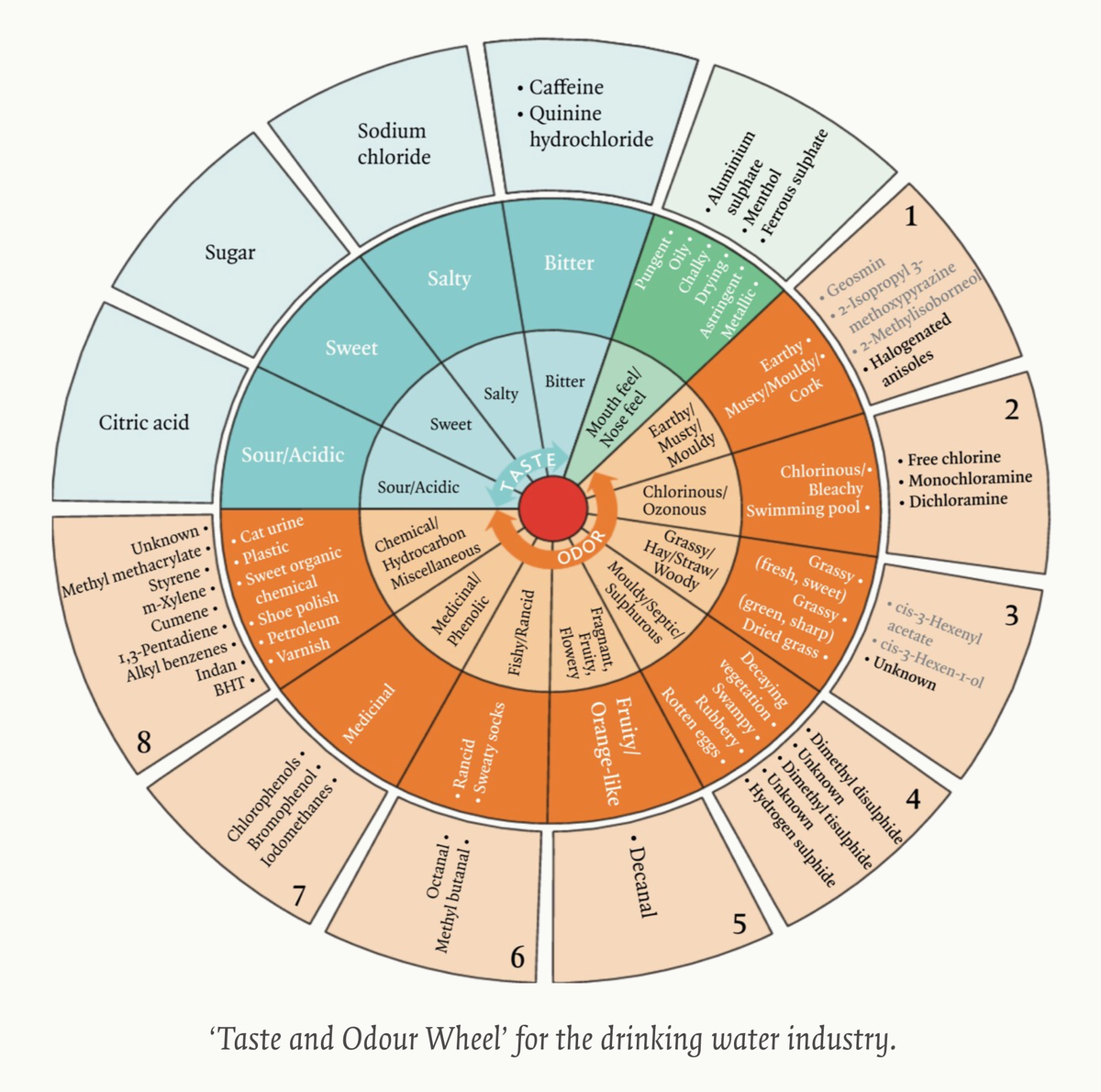

- "Story of Eau", Steven Shapin, London Review of Books. Mostly I remember the Taste and Odour Wheel at the top of this post.

- "The Hard Thing 5: The Myth of Platform Biotech", Anna Marie Wagner. I remember this piece for a diagram, too:

[1] Looking back on this list, I'm sad it doesn't include anything from Scientific American or New Scientist or Quanta Magazine. I read each of them sometimes, so perhaps I'm forgetting a piece from the last two years that mattered to me. But they don't scratch the itch as often as the bloggers and the new magazines above. I'm also surprised nothing from The New Yorker stuck. The New Yorker should commission more science!

[2] All of these pieces are in English (skill issue on my part). Idle idea: are there science magazines that could be translated from other languages into English, by someone with the passion and time? Vice versa, for e.g. Asimov into other languages?

[3] For the bloggers above, click the links to read around and subscribe, should they appeal. For the magazines mentioned, here are links to subscribe: Works in Progress, Issues in Science and Technology, ProPublica, National Review, The Atlantic, The New Atlantis, Asterisk, Asimov Press, Nature, Science, and London Review of Books. Then, of course, there's The New York Times, The Washington Post, Vox, STAT, and BBC, though they tend to be better for news. And, hey, The Stanford Daily, too.

[4] Not to do with science writing, just writing: I love Erik Hoel's philosophy of blog maximalism, blogs embodying the good of the internet: "And this same reaction of 'I don’t even know where to look, or where to begin' in the viewer (here, reader) is what I think the very best of blogging should strive for. For you can't read a very good blog all at once." Relatedly, I loved Hoel's Sampling the 2024 blogosphere: Part 1. That Sunday morning coffee will go far.